What’s the Payoff — Love or Money?

Some of these profiled artists received highly specific training to pursue their endeavors. Others fell into them. For those who earn their living from their art, most agree it’s getting increasingly harder to do so.

Nevertheless, all feel passionately about their work, and they’ve got impressive pieces to show for it.

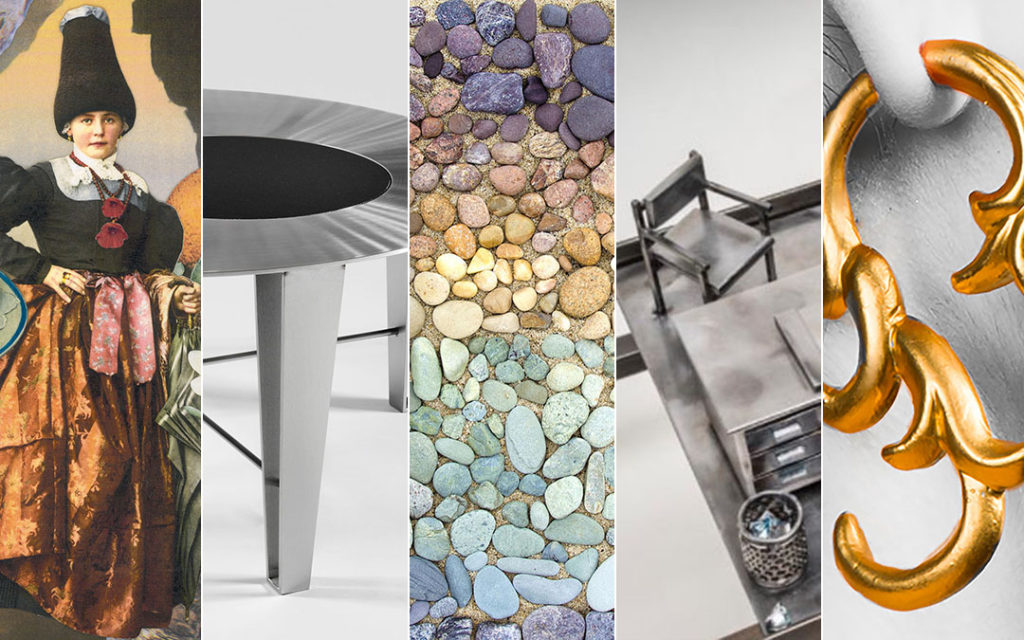

A sample of Jill Orlov’s work. (Handout photo)

Jill Orlov

Jill Orlov, 49, counts “The Borrowers,” a book-turned-movie about a tiny family that lives in the walls of a Victorian house, as one of her artistic work’s primary influences. Seeing her exquisitely crafted, minuscule rooms made of metal, it’s easy to understand why.

Shortly after earning a master’s degree in architecture from the University of Pennsylvania and starting her career, she left the profession and took a welding course, which led to a near obsession creating mini-vignettes from steel and other metals — some as dioramas in vintage wood boxes or drawers, others set within full-scale table frameworks.

The meticulously detailed rooms of metal (some of which include copper pots and pans the size of a thumbnail) can take Orlov well over 100 hours to complete; finished products range from $2,000 to $5,000. Her work, which has been exhibited at the prestigious National Building Museum in D.C., American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore and other venues, receives high praise but, in her own words, is a “niche market.”

“I could not do this risk-taking venture if I had other responsibilities,” admits Orlov, who is married without children.

Luana Kaufmann

Luana Kaufmann, 60, studied modern dance throughout her childhood and in college. After graduation, she spent about a decade creating and performing her own “multi-media dance/theater.”

But around 1992, says Kaufmann, “Collage found me.” She describes the transition as fairly fluid, suggesting that the former artistic expression informed her visual art. Dabbling turned full-time, as Kaufmann became immersed in creating collages out of found images, which she would meld with scissors, paper and glue. Scanning and meticulously printing these collages, they become archival pigment prints of museum-quality, explains Kaufmann.

The whimsical, almost fairy-tale, quality of her work suggests some sort of divine inspiration.

“It’s not like some glowing angel comes to me at 3 a.m.,” Kaufmann says. “But sometimes it does feel very magical.”

She creates her collages at night. “That’s my sacred time,” she says.

During the day, she often can be found in her Fells Point curiosity gift shop/gallery, Emporium Collagia, which she envisions as yet another “collage” — of her artwork, fine home goods and accessories.

Rick Rubin

Growing up in Bethesda, Rick Rubin, 59, loved to visit the National Gallery and spend time “making stuff” in his basement. After earning a dual degree in political science and art, Rubin moved to New York City and worked as a sculptor, while doing metalwork for architects and designers to pay the bills.

Finding greater satisfaction in design than art, he began to create a line of furniture pieces. Soon his custom-made furniture of wood, metal glass and stone was finding its way into selective design showrooms around the nation. After 20 years in New York, Rubin moved his studio to Baltimore, where the pace is slower and the space much less expensive.

Reflecting on his 30-year career, Rubin says, “It’s getting harder to make a living doing this.” He blames a decreased demand for high-end New Moon Table (Photo by Vince Lupo) craftsmanship, “Walmart-ization” of prices and the “Amazon-ization” of time frame. “The business model is going to have to make major changes,” Rubin says.

As he works to respond to the shifting market, there are some things Rubin doesn’t foresee changing. “We are a crew of four that has worked together for many years. The design and craftsmanship is done with care and love.”

Baroque double-sided earrings by Shana Kroiz

Shana Kroiz

Native Baltimorean Shana Kroiz, 50, is considered one of the country’s premier experimental enamelists. Her stunning fine art jewelry, both one-of-a-kind and limited production, has been sold at art galleries, museums, select arts and craft shows nationwide and online. Her jewelry lives in collections at the Smithsonian Design Museum and the Museum of Arts and Design, among others, and it all originates in her basement studio.

Although Kroiz’s business isn’t completely self-supporting — she balances it with the duties of motherhood — she says it could be. “But it is a hard business, especially more recently,” she says. “You kind of have to piece together a full income.” Over the years, Kroiz has supplemented her jewelry-making business with teaching, currently at the Baltimore Jewelry Center.

Her advice to those who want to follow in her footsteps?

“Take the classes. Do the research. Do the work,” she says. “Persevere. You’re going to get rejected. But you will love what you do.”

“Beach Rocks,” by Emily Gaines Demsky

Emily Gaines Demsky

Emily Gaines Demsky, 44, had no formal art instruction beyond some local adult workshops. But when her youngest child went to full-day kindergarten, she was freed up to explore an untapped passion for painting.

About a year later, in 2009, Demsky had her first show at the J.L. Pierce Gallery in Green Spring Station. That led to additional local gallery showings and sales, as well as the creation of a line of notecards and postcards based on photographs of beach rock arrangements.

Demsky describes her painting style as fresh, direct and loose; flowers and horizons dominate her subject matter. “When I go to paint, I actually say to myself: Paint freely and with abandon,” says Demsky, whose works range in size (4” x 6” to 38” x 50”) and price, between $60 and $3,500.

Demsky has declared 2018 the year she starts treating her art more like a business. But she admits that, if she suddenly had to support her family, “I don’t know exactly what that would look like.”